Food, Affinity, and Beyond

with Food Scientist Dr. Christy Spackman & Astronauts Nicole Stott & Barbara Morgan

I find that one of the strongest ways to understand something, truly understand it, is to contemplate all the sides, curves and bumps associated with it.

And if possible, to explore it to the extremes. So when the issue of Kinship was announced, I did what any good Food Editor would do.

I metaphorically ate the idea of kinship. Yes.

I unwrapped it from the layers of society, held it high up in the air and examined it. I brought it back down to investigate the aroma. It looked complex but smelled familiar. Not a good familiar or bad familiar. Just familiar. So, I popped it in my mouth and chewed.

Immediate. Explosion.

All the known flavors and emotions ranging from sweet and bitter to comfort and disgust gushed right out. The experience rapidly evolved too. History, cultures, stories, science and flavors I never even knew or thought about began seeping through. And then, we came to the edge. The unknown. Questions.

I like the edge. The edge is a powerful place to be when contemplating something. To know something. To feel. It requires us to step away from the comfort of the known and to push the limits just to make sure that what we understood couldn't be understood any further. That the bars we enclose ourselves in couldn't bend any more.

I knew kinship was going to be found and better understood in the extremes. And I was extremely fortunate to interview multiple women with dynamic world views who could explain the edges and intricacies of kinship and food.

–Karuna Kasturi, Food Editor

Nicole Stott

Creatively combining the awe and wonder of her spaceflight experience with her artwork to inspire appreciation of our role as crew mates here on Spaceship Earth

Image courtesy of NASA

Karuna Kasturi: As an engineer, artist, aquanaut, and astronaut, but ultimately as a human, what was your experience of food like in space, especially considering the many environmental factors at play, including gravity and a killer view to name a few?

Image courtesy of NASA

Nicole Scott: I really enjoyed the overall experience of eating in space. On both of my flights, as a crew, we always made a point of trying to have all of our meals together. The microgravity environment—floating—made eating and everything in space a fun adventure. Floating around the dinner table. Food floating. Silly astronaut tricks. Each of us had different music playlists and we’d bring those to dinner with us. All of us enjoyed eating and the opportunity to spend time together, floating around the dinner table, sharing stories from our day, solving the world's problems—all of those same kinds of things you do with your family around the dinner table. Except in space, “around the dinner table” is a little bit different, with the floating.

There has forever, I’d argue anecdotally, been this sense that astronauts' sense of taste changes in microgravity—that things taste bland. I think this is true for shorter duration spaceflight where your body doesn’t really have time to balance out from the fluid shift towards your head and to adapt to the new environment, but for the longer duration spaceflight the same people I saw putting Sriracha sauce on their food in space were the ones that were doing it on Earth. And like me, the ones who didn’t use Sriracha on Earth weren’t all of a sudden needing to use it in space.

Food/eating is one of those very human things. There’s pleasure in a good meal—even in space. There’s more to a good meal than the taste of the food—there’s the people you share it with, the place you’re in…the mix of both physical and psychological satisfaction.

Karuna: Though it is crew and mission dependent, your Commanders prioritized the importance of eating together on the International Space Station (ISS), that mealtimes should be a lot of fun, and your crew members valued that time together. Can you share some of these experiences and memories?

Image courtesey of NASA

Nicole: I’m thankful to have mission commanders who understood the significance of crew camaraderie—which included prioritizing time for us to spend together, like mealtimes. We shared our food. As an international space station we had foods from all of the different partner countries. We also ate our meals in different places as a crew—breakfast and lunch in the Russian Service Module galley and dinner in the US Node module. We were like a family.

Karuna: What was it like receiving “bonus food” from your family back on Earth? What did you receive and what connection did you feel to it?

Nicole: Bonus food was really fun. Usually a family will try to send something they know you really like but that’s not in the standard food kit, like your favorite candy or snack. My husband and son sent my favorite candy from a little shop in London—dark chocolate covered ginger. I love it on Earth but it was such a special treat in space. We all shared our bonus food with each other, too. It was pretty neat to see all the different kinds of “favorite” foods people have and what their families send to them.

Karuna: For longer missions, like ones to Mars, you say that food will need to be revolutionized, even psychologically and radically different. Can you tell me more about this?

Nicole: Right now on the ISS we have a food system that’s dependent on routine Erau poly from the ground and is also logistically demanding with respect to storage space on the station. The food also needs to be nutritionally balanced to counteract the impacts of microgravity on our bodies. When we travel further from the planet on a trip to Mars we won’t be able to use this same food system—a relatively small spaceship, on a many months long trip to Mars. We will need to revolutionize our food system. I imagine we might need to consider some pretty drastic changes just because of the storage space limitations. We might have to consider radical changes to something completely different to what we consider a meal on Earth—maybe even something like a pill or small food items that provide the full nutritional complement and then supplement with psychological measures like music and smells and colors to stimulate the satisfaction we get from the mix of foods we’re used to on Earth.

Karuna: You mentioned that when in space, while on this mechanical life support, there was an acute awareness of one another amongst your crew mates, that on a basic level you knew you were going to be taking care of each other. You felt it served as a peaceful and successful model. What can we learn from this kinship, here on Earth?

Nicole: I think we can learn about the ultimate interconnectivity of everyone and everything we share our planet with. We can acknowledge the model of living as an international crew on a space station is a model for how we can and should be living like crew mates here on Spaceship Earth.

Karuna: What do you believe unites us as humans, especially amidst a pandemic, and what will continue to connect us as humans with the possibility of living on a different planet one day?

Image courtesy of NASA

Nicole: Food in some form will always be necessary for us as humans to survive—regardless of where we are in space. As mentioned earlier it is one of the basic requirements of the human in human spaceflight. We will have to plan our human spaceflights with even more consideration for the needs of the humans. Things that bring satisfaction and joy. Raising our awareness to the awe and wonder that surrounds us everyday (on ISS that was in a big way the life changing view of our home planet out the window). But it’s also things like music and art and photography and conversations with our family…

These same things are true for us here on Earth and will be true for us on other planets. During the pandemic we’ve been more isolated, but also given the opportunity to reintroduce ourselves to the awe and wonder that surrounds us in our own backyards.

Karuna: You have expressed that most who visit space come back to Earth wanting to share something about what they experienced. This need to connect it back to our humanity, and help with the progress of humankind. What do you want to share?

Nicole: I want to share the simplest and perhaps most compelling lessons I learned from my time in space. Perhaps it’s better to say lessons that I re-learned because I think all of us probably learn or know these things by kindergarten. They are: we live on a planet; we are all Earthlings; and the only border that matters is that thin blue line of atmosphere that blankets and protects us all. These three things are at the core of all we have in common. They are the drivers behind the need for us all to behave like crew mates, not passengers. And I believe we all should keep the lessons of the planet, Earthling, thin blue line present in our minds all the time. Allow them to influence the decisions we make in all areas of our lives.

Image courtesy of NASA

Christy Spackman

Studying the taste of water, how sensory science shapes people's interactions with the environment, and the creation of tastelessness.

Karuna Kasturi: What made you want to study food? What is your connection to it, what does food mean to you?

Christy Spackman: I study food because it's this wonderfully complicated thing that shapes lives from birth. My family history—like so many other peoples'—can be traced through tastes and smells that have shifted, but nonetheless link past, present, and I hope future. Food means hope.

Karuna: A large part of your research involves finding taste—can you tell us more about this?

Christy: Perhaps a better description is finding traces of where taste exists. Taste (read: flavor) and Taste (read: culturally shaped desires, likings) rarely come at researchers directly. Rather both show up in other things: starred reviews, grease stains on documents, menus, receipts. As such, the historical aspects of my research require being a bit of a detective, looking for clues for the less-obvious thing. In this, I join an amazing group of historians who are also looking for overlooked things. The ethnographic aspects of my research are a bit more straightforward: I get to hang out with people who are tasting things!

Karuna: What fascinates you most about humans and their bond with food? What concerns you?

Christy: I love the fact that we are made up of what we eat, that the molecules in our bodies are being constantly remade using the food we put into us. I wonder what other values, ideals, and attachments that science can't easily measure accompany those bits as we ingest them.

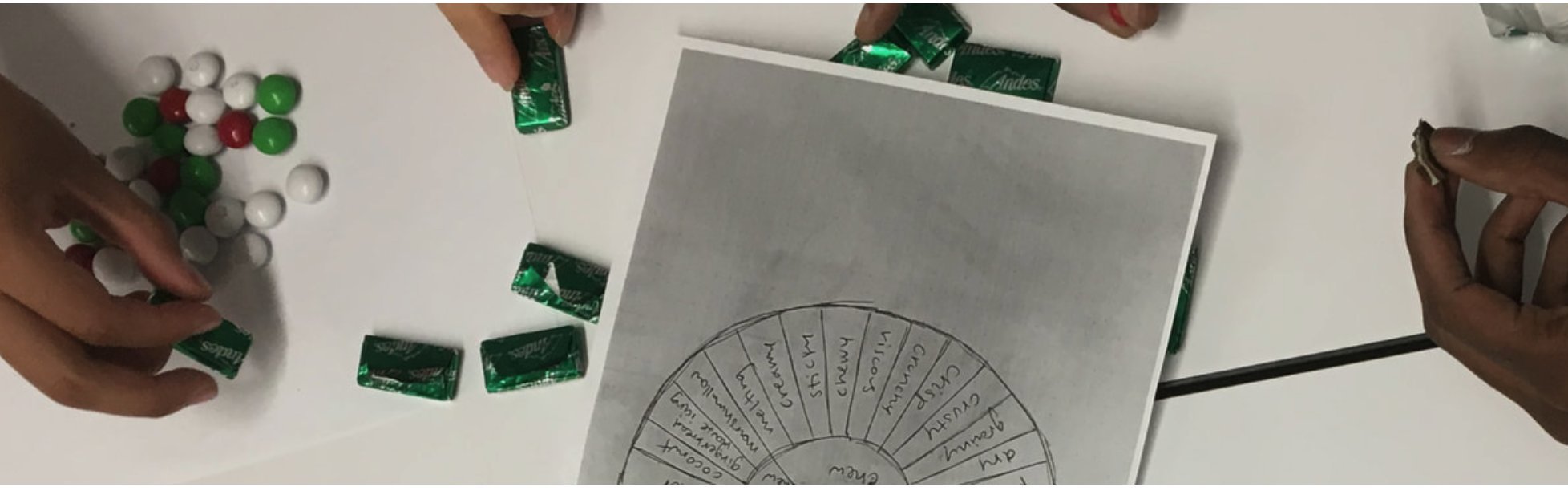

Images courtesy of Christy Spackman

Karuna: Your studies in food culture and science gives you in-depth knowledge of our interdependence with food. And not just human relationships, but almost any living thing. You spoke of microbial kin. What can you tell us about this?

Christy: Although humans have a long history of working alongside microbes (even when not conceptualized as such), it seems that the last few decades have witnessed a rapid expansion of interest. Thinking of microbes as kin is tricky, though: the relationship between us and the microbial other seems like it balances on a delicate divide between help and harm. Max Liboiron points out in their new book, Pollution is Colonialism, that kin can be both wonderful and crappy, helpful and harmful. I think of this dichotomy a lot when I read breathless accounts of how some supplement is going to fix our gut microbiota. There aren't quick fixes to our relationships with kin, but rather a lifetime of ongoing work to balance between our needs and those of our kin. Sometimes that might involve pretty radical steps (antibiotics come to mind). Often that might involve creating environments that promote a kin's best self.

Karuna: Is food as we know it only defined based on our survival and need for it? What do you think food would be or cease to be, without a human's need for it? What do you believe our relationship to food would be then?

Christy: Ha! This is a hard question. I think as a society, at least in the U.S., we are well beyond physiologic "survival" when it comes to food. Food is a substance that enables life at the most basic level, but then it becomes so much more: a marker of belonging, a way to create connection, an object of desire. What might it mean to have a body that doesn't need food at all? That seems to be something that would completely cut off our corporeal selves from the rest of the environment around us. I wonder if it would completely divorce us from the fact that we are part and parcel of nature. Would we still put our hands in the soil if it didn't produce food?

Image courtesy of Christy Spackman

Karuna: What is the best way for us all to respect food, and in doing so, respect ourselves? Especially knowing that so many starve for it and have unequal and unfair access to it.

Christy: I think the quickest way to gain respect for food, food production, and food systems is to try and grow some vegetables. In my case, it's become apparent that I would probably starve pretty quickly, or quickly re-adjust what I define as food: I'm very good at cultivating aphids and squash bugs, but very bad at cultivating squash. Growing things makes clear the intrinsic limits that shaped much of human existence, and why so many of the 20th century decisions that now seem disastrous were taken. Pesticides? Really great at increasing harvestable food. Industrialization? Great at preserving food beyond its season. Genetic modification? Allows novel intervention in foods to address disease (while also promoting profit). These things that are certainly open to critique are also things that promised a future of more abundant food. They promised less famine. They largely delivered, even if the quality of what was delivered leaves something to be desired. Acknowledging those competing logics through cultivation is a good place to start building ones' own food politics.

Barbara Morgan

Astronaut, teacher, cosmic seed-saver

Image courtesy of NASA

Image courtesy of NASA

Karuna Kasturi: In addition to being part of the STS-118 Endeavour mission that continued the construction of the International Space Station, retired teacher (you never really stop being a teacher) and astronaut Barbara Morgan was also part of a mission that included transporting ten million cinnamon basil seeds into space. This assignment encouraged thousands of students across the country, and ultimately the world, to participate in engineering their own growth chambers using the seeds taken into space and comparing their development to our earth-based seedlings.

On a scientific level, this project, as well as others like Tomatosphere and SEEDS (Space Exposed Experiment Developed for Students), generated an incredible amount of data and findings from scientists and from budding young researchers from kindergarten to graduate school. But it did more than that. In the April 17, 1992 NASA press release, students, teachers, and parents discussed how they felt connected, united even, to the rest of the world through these plant projects.

Never underestimate the power a single seed can have on the world.

Christy Spackman

Christy Spackman is Assistant Professor, Art/Science Nexus, jointly appointed in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society and the School of Arts, Media and Engineering at Arizona State University. Her work examines how the overlooked work done by food and sensory scientists shapes people's interactions with the environment. She's especially interested in the management of flavors. A desert transplant rooted in a messy multi-generation diasporic history, Spackman is a baker, candy maker, and fermenter of things. Learn more at christyspackman.com.

Nicole Stott

Nicole Stott is an astronaut, aquanaut, and artist, and now author of her first book Back to Earth What Life In Space Taught Me About Our Home Planet – And Our Mission To Protect It. She creatively combines the awe and wonder of her spaceflight experience with her artwork to inspire everyone’s appreciation of our role as crewmates here on Spaceship Earth. Nicole is a veteran NASA Astronaut with two spaceflights and 104 days living and working in space as a crewmember on both the International Space Station and the Space Shuttle. Personal highlights of her time in space were performing a spacewalk (10th woman to do so), flying the robotic arm to capture the first HTV, working with her international crew in support of the multi-disciplinary science onboard the orbiting laboratory, painting a watercolor (now on display at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum), and of course, the life-changing view of our home planet out the window. She is also a NASA Aquanaut. In preparation for spaceflight, she was a crewmember on an 18-day saturation dive mission at the Aquarius undersea laboratory.

Nicole believes that the international model of peaceful and successful cooperation we have experienced in the extreme environments of space and sea holds the key to the same kind of peaceful and successful cooperation for all of humanity here on Earth. She is the founder of the Space for Art Foundation—uniting a planetary community of children through the awe and wonder of space exploration and the healing power of art. Nicole is a graduate of Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and the University of Central Florida, and she is an avid SCUBA diver and instrumented rated private pilot. She lives in Florida with her husband, son, and two dogs. Follow her on Instagram @astro_nicole and @spaceforartfoundation, and learn more at npsdiscovery.com and spaceforartfoundation.org.