Latent

by Angelea Heartsong-Redding and Amanda Thomas

“…The mingling of Asiatic blood with European or American blood produces, in nine cases out of ten, the most unfortunate results.” -President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, 1925

In 1941, war seemed imminent with Japan. President Roosevelt assigned Curtis B. Munson, a representative of the State Department, to determine the degree of loyalty among residents of Japanese descent. The investigation concluded that there was no Japanese 'problem' or threat, and should have conclusively put to rest the idea of Japanese sabotage in the United States.

In early 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized military commanders to imprison people they thought posed a threat to the country.

"I am determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must go to camp." -Colonel Karl Bendetsen, Wartime Civil Control Administration, 1942

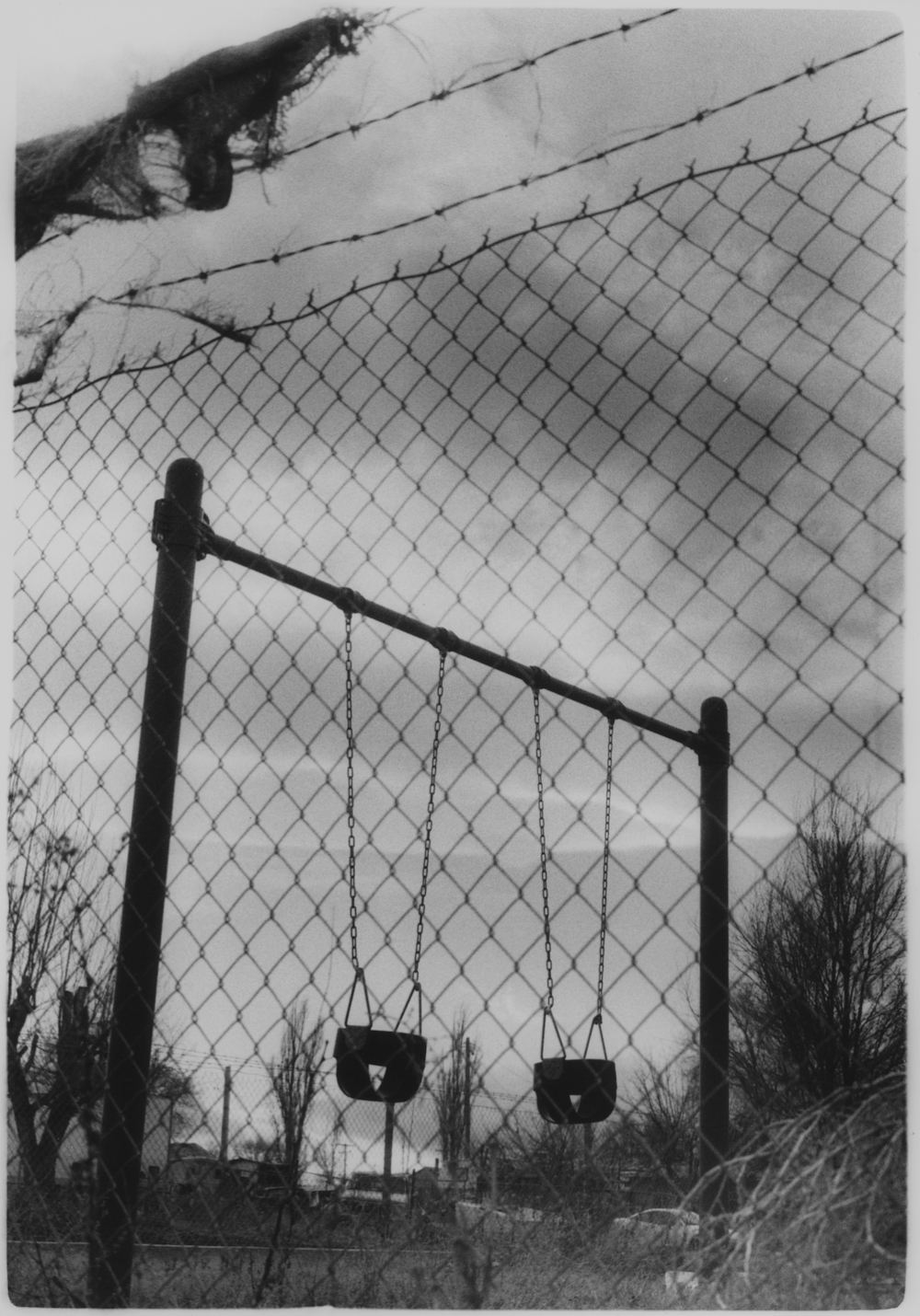

Locked In, Locked Out

Japanese Americans were ordered to take only those possessions they could carry and report to a central point in their neighborhoods from which they would be taken to an "approved destination."

For thousands of Japanese American homeowners and small business owners, moving out also meant selling out — quickly, and at an enormous loss. The total value of the property loss has been estimated at as much as 1.3 billion dollars. Net income losses may have been as high as 2.7 billion dollars (in 1983 dollars).

Japanese Americans were sent to Civilian Assembly Centers -temporary camps often located at abandoned horse tracks, where internees were made to stay up to 6 months while the military built relocation camps in various inland locations. The living arrangements at these relocation camps would be considered inhumane by modern standards.

“We walked in and dropped our things inside the entrance. The place was in semidarkness; light barely came through the dirty window on the other side of the entrance... The rear room had housed the horse and the front room the fodder. Both rooms showed signs of a hurried whitewashing. Spider webs, horse hair, and hay had been whitewashed with the walls. Huge spikes and nails stuck out all over the walls. A two-inch layer of dust covered the floor... We heard someone crying in the next stall.” -Mine Okubo, describing the Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno

Many families were separated because the relocation was rushed and messy. Families in this situation had to petition to rejoin their family. Not all of these requests were successful.

More than 120,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry were uprooted from their homes. Their final destinations would be one of 10 camps — "instant cities" — constructed by the WRA (War Relocation Authority) in seven states. Deeply isolated from the rest of America, these internees — 65 percent of whom were American citizens — would spend up to four years imprisoned.

“We were American citizens. We were incarcerated by our American government in American internment camps here in the United States. The term ‘Japanese internment camp’ is both grammatically and factually incorrect.” -George Takei, Internee, 2016

Castle Rock from the Camp

Set on over 7,400 acres, the Tule Lake Segregation Center included infrastructure typical of an average town: a post office, high school, hospital, cemetery, factories, warehouses, sewage treatment plants, and over 3,500 acres of irrigated farmland. During its four years, nearly 1,500 babies were born and over 330 people died. At its peak capacity, Tule Lake was home to more than 18,000 internees housed and a battalion of 1,000 military police in armored cars and tanks.

The camp had 144 administrative buildings, 518 latrines, and 1,036 hastily built barracks, with tarpaper walls and no amenities. They were hot in summer and cold in winter. A visiting judge noted that prisoners in federal penitentiaries were better housed.

Show Me the Way to Go Home

In 1943, every resident in the internment camps was required to complete one of two questionnaires misleadingly entitled "Application for Leave Clearance" to distinguish whether they were "loyal" or "disloyal."

Question 27 asked, “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?”

Question 28 asked, “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government, power, or organization?”

Many internees feared this question was a trap. Would a "yes" answer indicate that they had once sworn allegiance to Japan? Some refused to answer, or answered "no" to both questions, as a matter of principle. This questionnaire caused much turmoil within families. In some cases, all family members agreed to answer “no-no” in order to ensure that they remained together, even if that meant imprisonment in the Tule Lake Segregation center.

"This business about proving our loyalty -- when they first asked us those questions, I thought: My God! I didn't know how to answer. It just struck me as stupid. Why should I have to answer that? We saluted the flag every morning, and to ask us that.... it just ticked us off that we would be asked such a question right in the camp." -Jack Matsuoka, Internee, 1988

Those who answered “yes-yes” were moved out of Tule Lake, and those who answered “no-no” or deferred were branded as disloyal and moved to Tule Lake from the other nine camps. The influx of internees from other interment camps caused overcrowding. Most of the “no-nos” were kept in camp until several months after the end of the war.

Tule Lake initially had six guard towers, but by the end of its transformation into a segregation center, it had 28 towers supported by eight tanks and a copious number of machine guns.

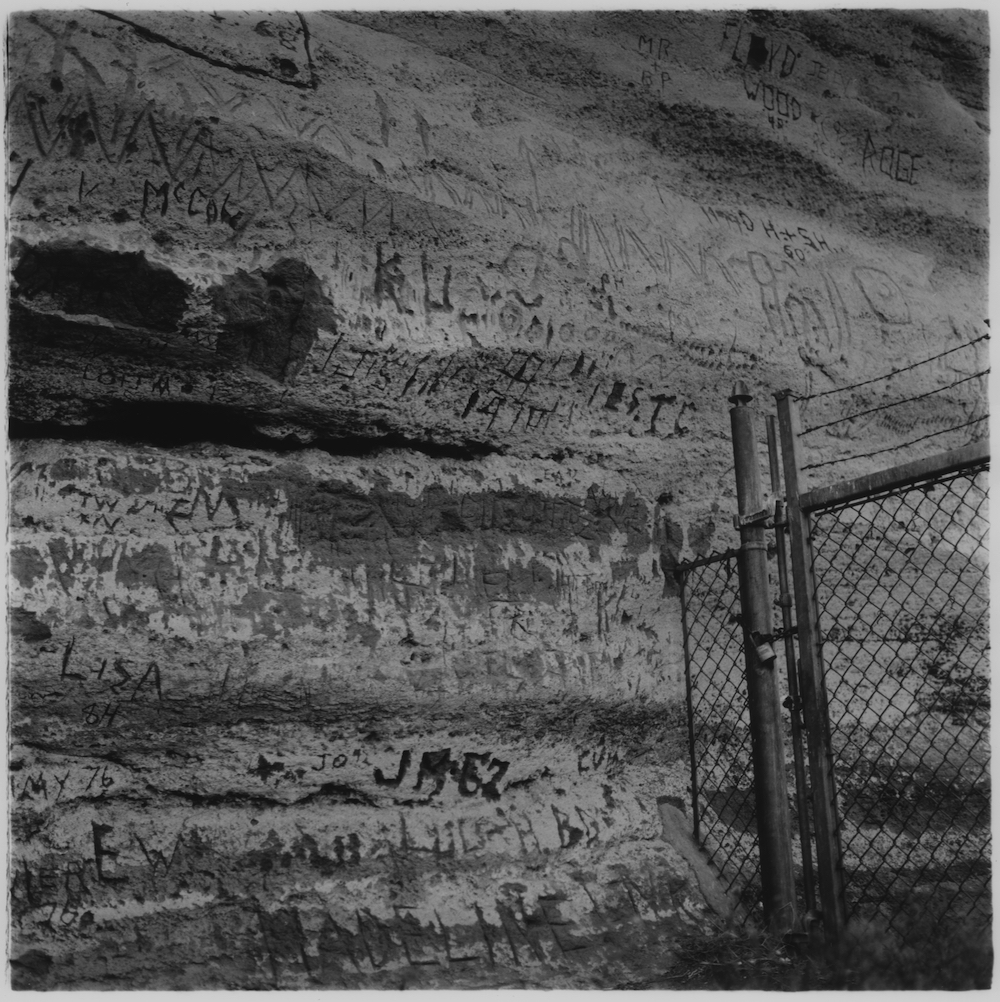

Inside the Jail

Under Martial law, a jail enclosed with fences and guard towers was built to hold internees who resisted. It contained six cells, a mess hall, and a latrine. Meant to hold 24 prisoners, the jailhouse was often overcrowded with 100 men. This “prison within a prison” completely isolated the “troublemakers” from the rest of the population.

Today, few of these buildings still stand: a small part of the Military Police Compound, over 1800 feet of barbwire-topped fence, and the original jailhouse, littered with graffiti, including names, dates, poems, and drawings. The cell walls bear witness to the inmates’ struggles during one of the saddest chapters of American history.

Jailhouse — Too Heavy To Be Stripped Away

Agriculture wasn't incidental at any of the incarceration camps. Many of the new WRA administrators came right from the Department of Agriculture. Camp locations, though usually in inhospitable places, were often chosen for their agricultural potential. The government's intention was to improve the land for after the war.

Each of the 10 incarceration camps nationwide had working farms whose stated purpose was to feed the incarcerated. Despite its dusty, snowy, windy climate and short growing season, the former lakebed was very fertile and Tule Lake produced a surplus. Some was sent to other camps, but camp administrators also took crops grown by these imprisoned Japanese American workers and sold it on the open market. When the Tule Lake camp opened, eligible men who refused to work were threatened fines.

Panorama

The history of the Tule Lake camp was marked by "turmoil, idleness, impoverishment, and uncertainty," in the words of one resident. Strikers protested working conditions, riots broke out over food distribution, and the stockade quickly filled with discontented men. Authoritarian tactics employed by security personnel made "martyrs" of protestors and increased agitation. Of the 18,422 people finally incarcerated at Tule Lake, 69 percent were citizens, most of them children. 39 percent had requested repatriation or expatriation to Japan, 26 percent had answered the loyalty questionnaire "unsatisfactorily," and 31 percent were family members of “troublemakers.”

Tule Lake officially closed in May 1946, seven months after the war ended, sending thousands of Japanese Americans out on their own to find housing and jobs with little money and in a society still prejudiced against them. The WRA gave each evacuee $25 and fare to Sacramento. After all those years spent imprisoned, it was difficult to decide where to go. Most had nothing left in their former homes. It was hard to put their lives together. The internees showed remarkable courage and dignity for overcoming the chaos of forced relocation, internment, and release.

“Finally getting out of the camps was a great day. It felt so good to get out of the gates, and just know that you were going home…finally. Home wasn't where I left it though. Getting back, I was just shocked to see what had happened, our home being bought by a different family, different decorations in the windows; it was our house, but it wasn't anymore. It hurt not being able to return home, but moving into a new home helped me I believe. I think it helped me to bury the past a little, too, you know, move on from what had happened." -Aya Nakamura, Internee, 2000

Barrack

What remained of the camp was empty barracks and thousands of acres of rich farmland, cultivated by the internees. The Bureau of Reclamation sold homesteaders surplus equipment and buildings from the segregation camp in a lottery system. Each was eligible to receive a 20x100 foot barracks for $300, and many barracks are still in use. This lottery was not extended to the Japanese Americans of the Segregation center.

Lottery Winnings

Camp Tulelake was constructed in 1935, originally to house Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) recruits, but it became a part of the Tule Lake concentration camp history in March 1943 after several hundred men imprisoned at Tule Lake refused to answer the infamous loyalty questions.

Initially imprisoned in county jails, they could not be held indefinitely for refusing to answer a questionnaire. Protestors were quickly moved to Camp Tulelake where the rule of law did not apply and imprisoned for months under armed military guard.

“They got to the point where they said, ‘Okay, we’re going to take you out.’ And it was obvious that he was going before a firing squad with MPs ready with rifles. He was asked if he wanted a cigarette; he said no… You want a blindfold? … No. They said, ‘Stand up here,’ and they went so far as saying, ‘Ready, aim, fire,’ and pulling the trigger, but the rifles had no bullets. They just went click.”-Ben Takeshita, recounting his brother’s ordeal at Tule Lake, where he was segregated for causing trouble

Camp Tulelake was used again as housing for strikebreakers. Following an accident where an inmate died, many internees went on strike, refusing to harvest ripening crops as leverage for their demands. To break the strike, internees from other WRA camps were brought in for the harvest. To protect them from hostility, the strikebreakers were sheltered away from Tule Lake, at nearby Camp Tulelake.

Camp Tulelake

From 1944 to 1946, Camp Tulelake was a POW camp for 800 German soldiers sent by the U.S. government in response to a plea from the Tulelake Growers Association seeking farm labor. These POWs were welcomed and given relative freedom to travel without guards to their paid farm jobs, and earned more than the American citizens imprisoned at the concentration camp. This episode offered a powerful example of the perverse logic of racism— locals welcomed the white German POWs, allowing them to work their farms, date their daughters, and eat at their tables, while American citizens with Japanese faces were treated as dangerous enemies.

“You are kidding yourself if you think the same thing would not happen again.” -Justice Antonin Scalia on the internment of Japanese Americans, 2014

Abandoned Migrant Worker Housing

A need for cheap labor also inspired the Newell Migrant Center, built in 1972 on the site of the internment camp. The complex contained 47 two bedroom cabins, each a mere 448 square feet. These are no longer in use, but 40 new apartments are now on the site.

Even with this available, many migrant workers struggle to find housing. Thousands of seasonal workers come to the Tulelake area, many sharing cramped trailers or finding other means.

Housing shortages for migrant workers are common, and proposed projects often face resistance from local communities. Many areas have massive tent cities reminiscent of dust bowl era camps. Some are in labor camps run by farm owners. While there are laws in place, enforcement of housing standards for migrant workers is generally lax. Workers housed by employers are unlikely to organize for fear of losing their jobs. Additionally, more than half of farmworkers in California are undocumented and under constant threat of deportation.

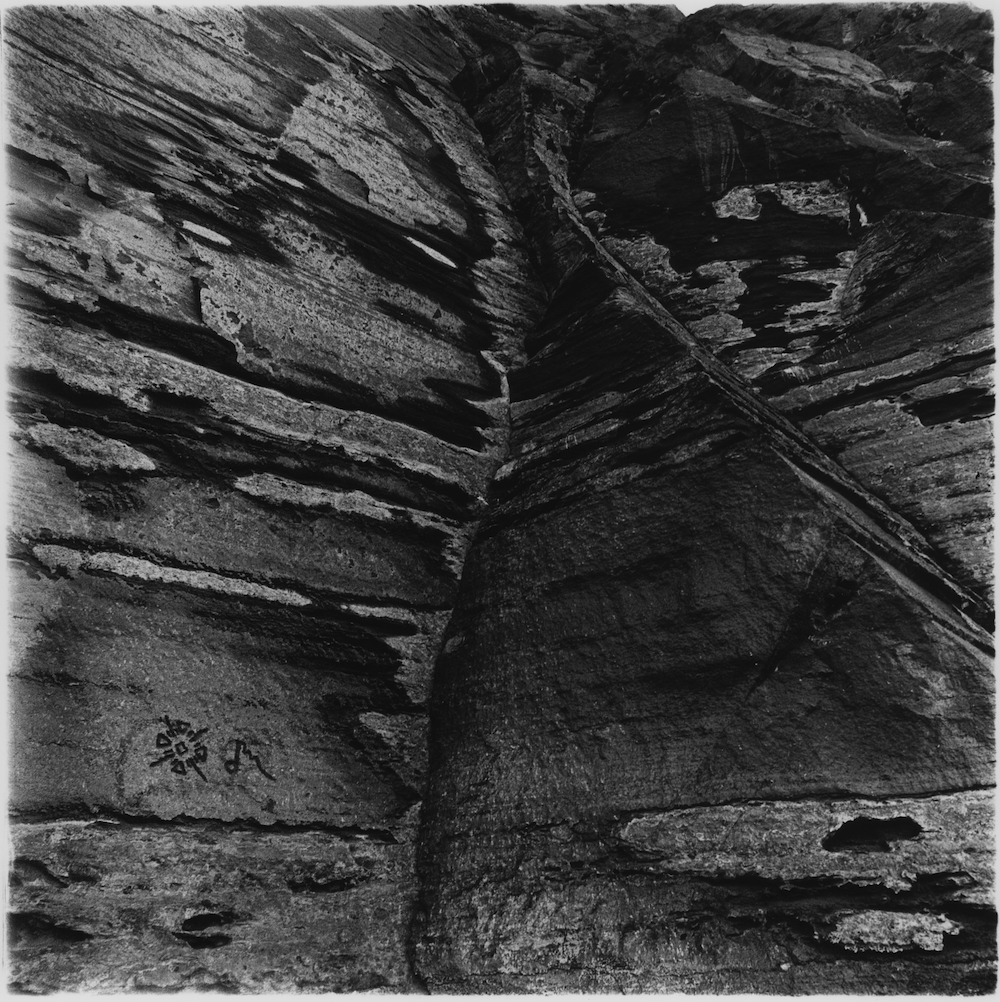

3.8 miles from the Segregation Center lies Petroglyph Point, a massive rock outcropping that was once an island surrounded by the shallow waters of Tule Lake. The Modocs and their ancestors paddled up to the rock face for thousands of years, carving and painting symbols into the stone. Estimated ages of the petroglyphs here go back as far as 6,400 years.

Petroglyph Point

The draining of the lake for agricultural projects in 1906 exposed the lake bed. Subsequently, harsh winds blow abrasive dust from the lake bed, eroding the petroglyphs. The site has also been heavily vandalized over the years.

Defaced

The meanings behind the unique petroglyphs were largely lost in the fracturing and exile of the tribe following the Modoc war, but the site is still a place of spiritual significance. A plaque at the site indicates that this is where Kamookumpts, the creator of the world, sleeps.

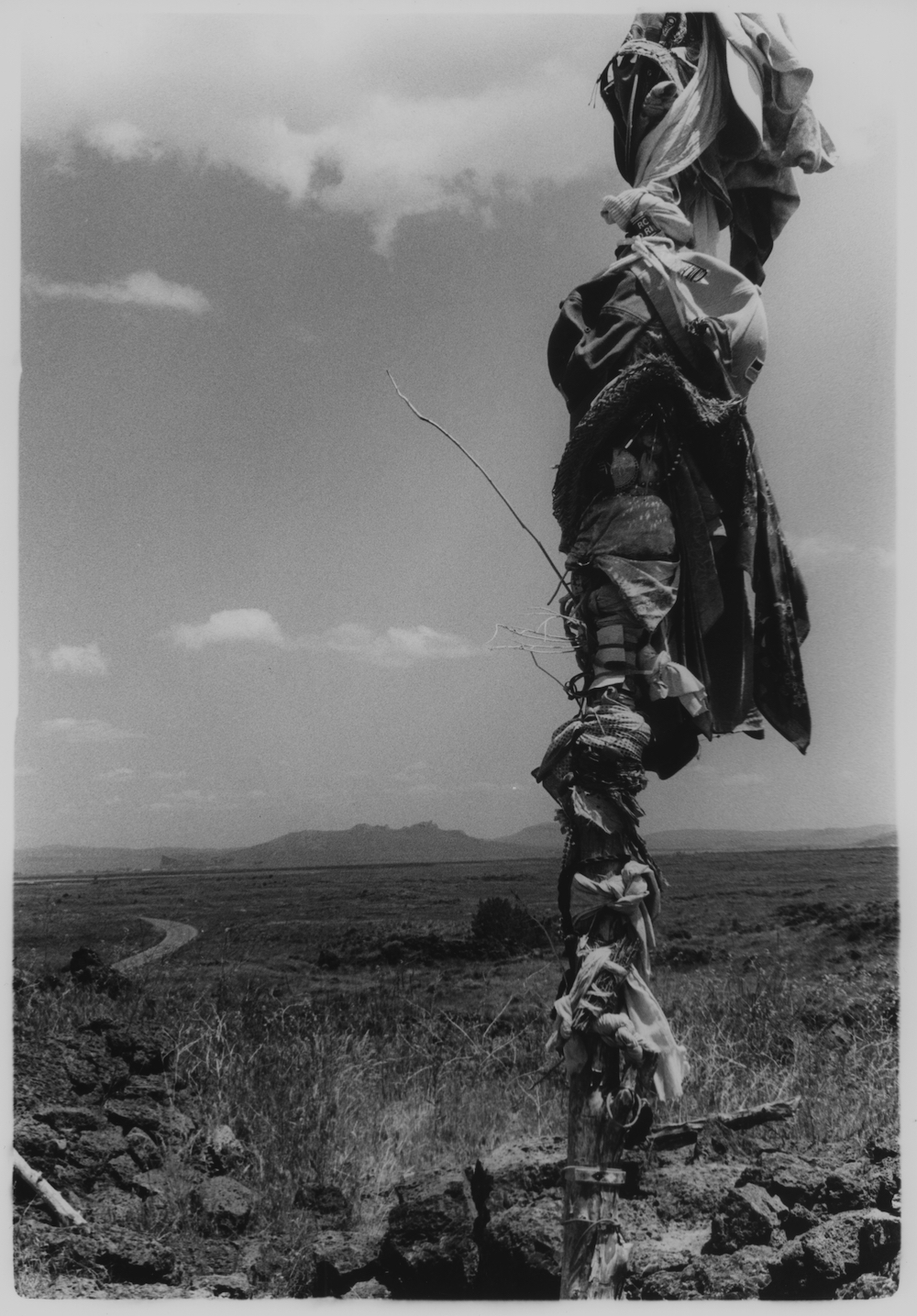

A Road Through Tulelake — North Towards Castle Rock

The Modoc traditionally inhabited the area of the Klamath Basin from the Lost River south to Mt. Shasta. They lived in small bands and villages, following the seasonal bounties of the land. Each band was its own autonomous entity with no central governance between them.

The first contact from European-Americans was in the 1820’s, when trade was established between the neighboring Klamath tribe and the Hudson Bay Company. Regular contact did not occur until the completion of the South Emigrant Trail in 1846. This trail caused a huge influx of white settlers into the region. The Modoc were, at first, helpful and friendly with the settlers, but as more came, the tribes lost access to their lands on which they hunted and gathered food. Many were starving. Additionally, in 1847, a significant portion of the tribe died of smallpox. Conflict escalated, and there were attacks on both sides.

“They have neither the intelligence, the industry, the moral habits, nor the desire of improvement which are essential to any favorable change in their condition. Established in the midst of another and a superior race, and without appreciating the causes of their inferiority or seeking to control them, they must necessarily yield to the force of circumstances and ere long disappear.” -President Andrew Jackson on Native Americans, 1833

In 1864, the Modoc chief Kintpuash approached the Indian Agent of the area to draw up a treaty for a reservation near Tule Lake. The Office of Indian Affairs, however, put all of the local tribes on the same reservation on Klamath land. The tribes were to get only 2 million of the 20 million acres of land they inhabited, plus 15 years worth of supplies to get started. The promised supplies, however, took years to start coming in, and were unfairly distributed, with the larger Klamath tribe often getting the Modocs’ share. Tired of trying to find their place on the reservation, Kintpuash led a band of Modocs to return to their home along the Lost River. They lived in relative peace there with settlers for about 2 years, but conflicts arose and intensified. Kintpuash’s band was pressured to return to the reservation. When he refused, the army was sent in to force them back.

“The only good Indians I ever saw were dead.” -General Philip Henry Sheridan, 1869

Their village was burned to the ground and they fled toward the shores of Tule Lake. With all their possessions left behind, they took to their boats and went across the lake to hide in the lava beds. Other bands joined them there. With about 150 Modoc people there, 100 of them women and children, the ratio of military to Modoc fighters was about 20:1, but they were supported in their knowledge of the harsh, rocky terrain. They had had traditionally hunted there, storing food in the ice caves and using others for lodging. They constructed barriers in addition to the naturally existing ones. They were able to fend off the US army for a remarkable six months.

Refuge

As more military forces were sent in, the defense became untenable. They were forced to abandon the stronghold and leave behind those too old and infirm to carry on to the next place. When the army made its way into the stronghold, those left behind were killed.

Divisions began to take hold in the tribe. A portion of the Modoc turned themselves in, and pledged to help capture Kintpuash in exchange for amnesty.

On June 4th, 1873, Kintpuash’s band gave themselves up. They were held in a stockade for four months. Kintpuash and three others were publicly executed, two were sentenced to life in prison, and the rest of the band were put on a train in cattle cars and exiled to Oklahoma.

Memorial

A mere 27 years from the arrival of European-American settlers, the Modoc tribe went from thriving to decimation, their home taken and way of life destroyed. The US military spent nearly half a million dollars on the war, and many lives were lost on both sides. The land that Kintpuash had requested for his people would have only cost $20,000.

“I am but one man. I am the voice of my people. Whatever their hearts are, that I talk. I want no more war. I want to be a man. You deny me the right of a white man. My skin is red; my heart is a white man's heart; but I am a Modoc. I am not afraid to die. I will not fall on the rocks. When I die, my enemies will be under me. Your soldiers began (fighting) me when I was asleep on Lost River. They drove us on these rocks like a wounded deer. I have always told the white man heretofore to come and settle in my country; that it was his country and Captain Jack's country. That they could come and live there with me and that I was not mad with them. I never received anything from anybody, only what I bought and paid for myself. I have always lived like a white man, and wanted to live so. I have always tried to live peaceably and never asked any man for anything. I have always lived on what I could kill and shoot with my gun, and catch in my trap.” - Kintpuash

There is a Modoc tribe of Oklahoma to this day, federally recognized in 1978. The other Modoc bands are now part of the Klamath tribes, along with the Klamath and Yahooskin. They managed to adjust their way of life and become relatively prosperous. In spite of this, or perhaps because of it, federal recognition of the Klamath tribes was terminated in 1954, with devastating consequences. It was reinstated in 1986. The current Klamath reservation is 308 acres. The Klamath tribes have retained water rights in the area, which is a source of conflict between the tribes and farmers in the region to this day.

Angelea Heartsong-Redding

Angelea Heartsong-Redding is a photographic artist based out of rural northern California. Her artistic practice is deeply affected by her lack of a traditional upbringing and her longing for the relationship of home - the link to a place of being - and this profoundly influences her work. She says, “I am searching for the connection between history, home and experience; between human and nature, and I am always chasing the light.”

Amanda Thomas

Amanda Thomas is a multidisciplinary artist based in northern California. As a single parent, her practice, processes, and ideas are heavily influenced by the demands of her life. In her work, this manifests as a recognition of the myriad ways there are of living, a cry for changes in the social order, and a celebration of the resilience of the human spirit.

![[Overlooking the Shoreline of Tule Lake]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5329d1f0e4b0bd8ef0319189/1534393807334-FCWRLB5VCG1O1U4TAVOQ/%5BOverlooking+the+Shoreline+of+Tule+Lake%5D)