Little Red Riding Hood, or, How the Patriarchy Hurts Men, Too

Jan Underwood

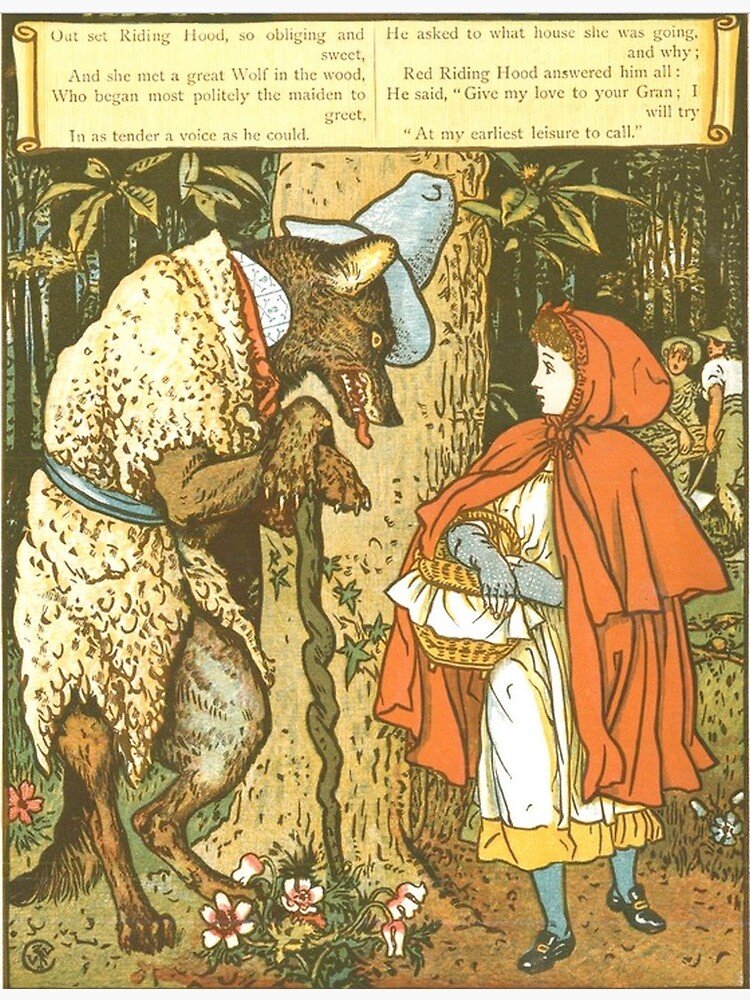

You know the story. Grandma Riding Hood was sick; Mama sent Little Red through the woods with a basket; the Wolf intercepted her—you have it memorized.

What a curious name, though, no?

“Little” our protagonist certainly was—not more than six or seven years old. But why was she wearing fancy equestrian gear while setting out on foot? If we assume our tale took place in the Middle Ages, which European fairy tales vaguely seem to, I’m afraid this part of the story is a total anachronism. Riding hoods were not invented till the 18th century. Furthermore, sumptuary laws forbade citizens to dress above their station. I kid you not! From a thousand years before our tale begins, if you were a laborer, your sartorial choices were restricted to “laborer” fabrics and styles. Still—these laws were difficult to enforce, and it’s possible our heroine was a bit rebellious. And moreover, it’s the writer’s story, and she can do what she wants with it. I’m letting LRRH keep her anachronistic getup, for the metaphoric value it carries. It may come up again, you know, this matter of disguises, rebellion and identity.

Well!—What about the “red” part? Red is the color of blood and flesh, sexuality and violence, hypersexualization of women and girls, rape and murder. Because of course before he ate Little Red, the Wolf raped her. You knew that, right? You knew it even though you didn’t know you knew it. This story is so familiar to you, you’d forgotten what it meant. It’s been hiding in plain sight.

I don’t happen to know what she was called at birth, but from the time of the Wolf incident, LRRH went by Renee. (That’s French for “reborn,” in case you were wondering.) The two strong women raising her were very much at the center of Little Red’s heart and hearth. Nevertheless, her mother sent her, vulnerable and alone, through the woods—another metaphor. Here’s the thing: mothers have never been able to protect their daughters from male violence. Mothers send daughters into danger with only frail advice—stay on the path; don’t talk to strangers—putting the onus on their daughters not to be raped and murdered.

Off went wee Red into the forest, like every generation of girls before her, metaphorically speaking. The Wolf tricked her, ran ahead to Grandma’s house and raped and ate Grandma. What? You didn’t realize he raped Grandma? Even though she was post-menopausal and widowed—that is to say, purportedly post-sexual—and sick to boot? Well—rape isn’t about allure. You know that. He raped the very much pre-sexual as well. Rape isn’t about allure; I know you know that.

The story as you learned it ended when the Woodcutter came along. You haven’t heard the Woodcutter’s backstory, though. And while I do intend to center this retelling on Little Red herself, I hope you’ll permit me to speak to my story’s subtitle by relating a little about its male lead.

This particular woodcutter was a Nice Enough Guy—and as Nice Enough Guys tell us often, not all men are rapists. Still, he found himself limited by the social roles on offer. His choices pretty much came down to woodcutter or wolf—or, in the framework of Glick and Fiske’s 1996 Ambivalent Sexism Inventory Scale, “benevolent” sexist or misogynist. What he could not be, publicly, was someone who envisioned other options.

Our Woodcutter—his name was Joe—could read a little, and fashion Pan pipes from hollow reeds. He wished there were someone in his life who remembered his birthday, but it seemed unlikely such a person existed. If there were someone in his life whose birthday he remembered, he would make her a Pan pipe. But the companionate marriage would not be (publicly) invented for another half-millennium. And though there were other woodcutters in the forest, they told dumb, lewd jokes and boasted about the girth of trees they felled. Joe did not show his pipes to them.

Then came the day when LRRH went skipping with her basket of wine and cake to her sick grandmother’s house.

Can I just interject here a minute?—because what a bizarre and implausible care package. Alcohol and sweets are contraindicated when you’re sick. Also, it’s unlikely the Riding Hoods ever encountered cake. Wine, sure, okay, and beer. Much local water was not potable, and a little hooch in your drinking-glass would diminish your chances of death by dysentery. Since I don’t see much metaphorical value in the traditional props of cake and wine, let’s say the child carried a bottle of lightly fermented, dilute beer, a jar of chicken soup, and some echinacea. Her mother put these things in a basket and sent her into the forest, metaphorically and literally, and there Little Red met the Wolf.

Now if I might—the Wolf has a backstory, too. He was a minor noble and had had an education befitting his station, consisting of Rhetoric, Logic and Latin. But he’d been born to a father who told him he would not amount to much. Also, he was dyslexic, and the other puppies made fun of him for it. As he got older, the Wolf became the huffingest, puffingest wolf around—trying, I surmise, to stop feeling like a punky little cub inside. And he bullied women most of all, physically and rhetorically. In fact, the thing Little Red would remember most clearly about her encounter with this damaged wolf was the exchanges with the Wolf that preceded her life’s worst trauma.

There were two interviews, as you will recall. First, as we’ve established, the Wolf garnered intel from LRRH and ran ahead to gobble Grandma. Then he appeared a second time, in Grandma’s dressing-gown. This subsequent conversation was the one that later most troubled Renee. How was it possible that she could have failed to recognize her own beloved grandmother? How could it be that, already primed by her first encounter with the Wolf, she was not on high alert when she entered Grandma’s room? Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.

The truth is that by the time LRRH got to Grandma’s house, she was indeed on high alert. She had had a peculiar conversation with the Wolf on the path, in which he’d asked impertinent questions like where she was going, what she had in her basket, and where her Grandma lived.

Now I’m going to have to interrupt again, because the scene cries out for explanation. This term “European Middle Ages” covers a lot of ground: a millennium, more or less, in territory stretching from Greenland to Siberia. Fairy tales as they have come to us were penned not in the Middle Ages, but later, and they project a later time’s notions of an earlier time. Are we dallying about in Charles Perrault’s 17th-century French imagination? The Grimm Brothers’ 19th-century German one? Are we in Disneyland? The modern fairy tale is a mashup of several cultures and centuries, none of them contemporary with Red Riding Hood herself. I say it’s the writer’s story, and she can do what she wants with it—which is England, circa 1357.

Now Grandma appears to be a member of none of the medieval Three Estates—nobility, clergy or peasant. How is it that she owns a cottage and lives alone? In the first half of our chosen century, her circumstances would be implausible indeed. But by mid-century, the Black Death had wiped out as much as half the population of the continent—a sorrowful thing, to be sure, but one that opened up possibilities as well. Workers gained bargaining power with their feudal lords; laborers could leave their fiefs; and women who survived their husbands found new opportunities to earn their fortunes manlessly.

In this burgeoning midcentury merchant class, as many as a third of English women—I kid you not!—lived out their lives unmarried. They became bakers, dairy maids, barmaids, artisans—and were permitted to inherit land so long as no male heirs were about. In this respect they had, for a brief post-plague period, more autonomy than English women would for several centuries afterward.

Grandma and Mama Riding Hood supported themselves brewing beer. They had each inherited from Grandpa (who does not figure into this tale, having died of plague in 1352) a cottage and some land. For her part, the youngest Riding Hood expected to grow up enjoying a life of property ownership and self-employment outside the bonds of wedlock—free from both wolf and woodcutter, as well as from the statistical probability of dying in childbirth.

Meanwhile, here she was, standing beside her grandmother’s canopied bed, about to meet the Wolf a second time. She pushed the curtain aside and peered into the darkness. A large lump lay under the covers, rather larger and lumpier than the grandmother she knew.

LRRH had arrived at Grandma’s full of trepidation. She had felt, on the path some minutes earlier, that the Wolf had no right to demand her personal information. But, too, she was awed by his stature as an adult and a wolf, and she did not feel she could refuse him. She had, against her better judgment, answered politely and truthfully, hoping that good behavior would somehow shield her from harm. The Wolf had encouraged her to dillydally, picking flowers in the meadow while he loped away in the direction of Grandma’s cottage. All this was suspicious enough to raise doubts in Little Red’s mind. Then, when she got to Grandma’s house, everything seemed wrong: the unlocked door, Grandma’s unshapely bulk in bed; Grandma’s strangely deepened voice when she called to the child. Little Red approached the straw mattress with uncertainty. What she seemed to see in the close and windowless room did not reassure her: the hair that had sprouted on Grandma’s face; the shine of her incisors. And yet she did not trust her eyes and ears. She had been told that adult men (of both the wolf and woodcutter variety) were dangerous, but she had also been told that adult men were to be respected.

So she chalked up Grandma’s distorted mouth and gleaming yellow eyes to illness, soon to be cured with chicken soup. That Grandma fit so awkwardly in her gown, that Grandma’s ears were become so pointy, that these pointy, hairy ears stuck out at angles from her nightcap, aroused suspicions LRRH felt were not permitted to her.

For years afterward, it was those moments of wrestling with doubt and self-doubt, of standing on the threshold of her own judgment, trying to convince herself of what were likely lies, that were most indelibly stamped on Renee’s memory. In fact she felt great shame later for having chosen gullibility over good sense. But in time, that memory of indecision gave Renee another insight as well: Expectations could defy experience. People often doubled down on their beliefs, in spite of themselves.

She had little time to reflect on the contradictions in the moment, because as soon as she and the Wolf had conducted the brief, repetitive dialogue you know so well, the Wolf violated and swallowed Little Red whole. Then he groaned with discomfort, so full of women was he. The women were uncomfortable too, of course, cramped and drenched in digestive juices. At first they clung to one another for support, and then they kicked the Wolf from the inside, so that his discomforts multiplied and he began to yelp in a very unmanly way. Woodcutter Joe happened to be just then passing by, axe on shoulder, and he heard the commotion.

Even though he was a fairy-tale character, Joe marveled at the coincidence: he’d arrived at the critical moment and with the right tool for the job. (Little-known historical tidbit: Perrault’s version of this tale makes no mention of the Woodcutter, but ends with the death of LRRH. Moral of the story: Women shouldn’t put themselves in danger by living human lives. The Brothers Grimm added the rescuer and let him kill the Wolf. Moral of the story, foreshadowing Glick and Fiske: there are two kinds of men; women should let the one save them from the other).

Out stepped Grandma and Little Red, wet and disheveled, frightened and angry, holding hands. They looked from Woodcutter to Wolf and back again, and then at one another. Grandma said, “He could use some medical attention.” LRRH, with dexterous young fingers, sewed the Wolf up; Grandma gave him a little echinacea and sent him on his way. The Wolf’s brush with death and the big painful gash on his belly, they reasoned, was the natural consequence of his malfeasance, and perhaps in time his brush with death would give him some perspective. Some 770 years ahead of their time, the Riding Hood women had invented the concept of restorative justice.

The Riding Hoods invited Woodcutter Joe to enjoy some chicken soup and beer. Joe told them it was his birthday, and they sang the Happy Birthday song to him, somewhat tunelessly, more than 650 years before it was written. Then the women walked to Mama’s house, and Joe would not see them again for a long time.

* * *

As I’ve mentioned, LRRH—now Renee—had grown up expecting to live on her beer earnings. But the day came, about a decade later, when a strange man came along who had another notion.

That man appeared at the door of Mama’s cottage. Whether he was wolf or woodcutter I’m not sure. (The two can sometimes be hard to tell apart). He claimed to be the sole and rightful heir to the Riding Hood property as a son of Grandpa Riding Hood. None of the women had heard of him. He didn’t look a thing like Grandpa. He threw around some unfamiliar terms like de donis conditionalibus and feodum talliatum. He said the land, the two cottages and the brewing equipment were his, and that the women needed to shove off.

The Riding Hoods found themselves homeless and without means of support. Mama became a barmaid in the nearby village, and they moved into a squalid back room at the inn, but she could not support three people on her poor wages. She decided to send Renee alone and vulnerable into matrimony. Here’s the thing: Mothers have never been able to protect their daughters from marriage. Mothers send daughters into danger with only frail advice—cook a good stew; let him have his way—putting the onus on their daughters not to be raped and murdered.

Female marital consent would not be invented for another half-millennium, but Renee was certain she could and should dodge any matches her mother made. She was extremely wary of men, of both varieties. Could she become a nun? She could not. In the European Middle Ages, nuns came from aristocratic families. To enter religious orders, they had to pay the Church. I kid you not! Still, because she had been raped and eaten and emerged alive, Renee had a strong sense of self. Also, because she and Grandma had gone through trauma together, they were very bonded. Men might have most of the power in their land, but women had something men did not: each other.

It was good they had each other, because they now had little else. Since they’d moved to the inn, they ate only leftovers from patrons’ plates. Mama scurried after culinary flotsam and jetsam and set it aside for a late family supper. When she wasn’t rushing out with beer steins and trays of food, mopping and occasionally breaking up a fistfight, Mama scouted for a man to marry Renee. It was almost as disheartening a prospect for her as for her daughter, but marriage, she reasoned, was better than starvation. She looked the men over, and if any appeared stable and was able to pay his tab, she’d ask him if he needed a wife. Day after day she approached them, wolves and woodcutters both.

Meanwhile, the Wolf had been undergoing a transformation. After the fabled incident, his hunting days had come abruptly to an end. The scar of his incision hurt terribly when he ran and pounced. He lived on mostly on porridge and hung around the town square, where he got to know some other wolves. They were older; some were disabled vets. These old town-square wolves weren’t much impressed with our Wolf no matter what he boasted of. But neither did they bully him or tease him. They weren’t very interested in talking about conquests, and they shared their porridge with him. Little by little, he found he was impressed by them. They gave him ideas about other ways of being in the world.

He started mentoring at-risk puppies. This work, so new to him, got him to reflect on the things he’d done himself as a younger wolf. He thought in particular about Little Red Riding Hood and her Grandma, and how his brief, intense encounter with them was the catalyst for his metamorphosis.

At first, he’d held onto grievances: in his mind, it was their fault that he’d been cut open and lost his ability to hunt. But his time with the older wolves, and then the pups, changed him. He began to reflect on what the experience had been like for the Riding Hoods: how terrifying, how dreadful, how unfair. He wondered how they’d managed afterward and what they were up to now. Finally, he decided to seek them out and try to make amends. Around the time that the family moved to the inn, the Wolf, with encouragement from his friends, composed a letter.

You may remember that the Wolf had dyslexia. He labored over this writing. When he was satisfied, he hand-delivered it, taking the old path between the former Riding Hood cottages and cringing when he passed the spot where he’d met LRRH. He left the letter at Grandma’s door, not knowing, naturally, that Grandma no longer lived there.

The man who had taken over the Riding Hood property found the letter on his doorstep that evening. He didn’t know what to think of it, so he tossed it into a basket Grandma had left behind, and there it lay for many days.

Around this time, Woodcutter Joe happened to be working in that part of the forest. One day he came upon the familiar cottage and decided to pay his respects to Grandma, whom he hadn’t seen in all these years. Of course he didn’t know the house had been overtaken by the fellow who claimed to be a son of Grandpa Riding Hood. That fellow told Joe the women were gone, he didn’t know where. He wasn’t unfriendly, though; the axe over Joe’s shoulder—his general air of manliness—made the fellow feel on familiar ground. While they were standing there, the letter, tossed without a thought into the old basket, caught Joe’s eye. You will remember that Joe could read a little. “Is that—is that a letter to the Riding Hood women?” he asked. The other man shrugged. He didn’t know what it was and didn’t much care. The fact that Joe was literate aroused suspicion in him, and their chumminess cooled. Joe thought to offer to deliver it, if only he knew where the family had gone, but he was, as you know, sensitive, and he perceived the shift in his new acquaintanceship. He said in a gravelly voice, “I’ll take care of it, if you like,”—letting the implication hang that he might peruse the contents and, if they contained anything unhelpful to the current occupant of the Riding Hood home, make the letter disappear for good.

The other fellow paused. He could, of course, simply toss the letter into the fire himself. Wolf or woodcutter, I can’t tell, but certainly he thought it improper for women to be receiving letters. But some gleam of curiosity lay within him regarding the letter’s contents—the possibility that it contained something of benefit to himself. He cast a glance at Joe’s one slightly cocked eyebrow and decided that they had an understanding, man to man—woodcutter to woodcutter; wolf to wolf—and he agreed.

Now all Joe had to do was find out where the Riding Hoods had gone.

* * *

Unbeknownst to Joe, the women were also at this time seeking him. The tenth anniversary of their meeting him was approaching. They’d decided it would be good to visit Joe and thank him for his service all those years ago.

That same day, Mama found a match for Renee. As usual, she’d approached a group of diners finishing their meal. “Any of you gentlemen in need of a wife?” she asked as she pocketed their sixpence. “I have a daughter who’s of age.”

The men at the table commenced the usual round of crass jokes: they were in need, but their current wife would frown on it; could they swap their current wives for this younger one? and so on.

A stranger behind her tugged Mama’s apron strings. He’d been having a beer alone in the corner. “I could use a wife,” he growled. She turned with some hopefulness, but paled when she saw that the speaker was none other than the man who had seized her property from her—the man who had just months earlier been claiming to be her own half-brother, and uncle to Renee. “How old is the lass then, and is she a good worker?”

Mama took a moment to recover, as she grasped that the man did not recognize her. She was half-starved now and much changed. But in truth, the stranger had considered the Riding Hood women so much beneath his attention he did not remember what they looked like, and would not have known Mama if he’d run into her the day after annexing her home.

Mama opened her mouth to tell him, but changed her mind. “A very good worker, of sixteen years,” she said evenly.

“Good enough teeth?”

“Good enough.”

“I’ll be wanting to inspect her, then,” said the stranger.

They made arrangements for the two to meet the following day. Mama had half a plan. Renee would supply the other half.

* * *

That evening the three women went to seek the Woodcutter. They knew roughly where he lived, in their old neck of the woods.

They found Joe on the stoop of his cottage, fashioning Pan pipes from hollow reeds. He was delighted to see them—and rather stunned, because he now had a letter in his possession addressed to them. He had not broken the seal, so he did not yet himself know what it contained. With the women’s permission, he unsealed it and read it aloud. What was done could not be undone, the letter said. But the Wolf had changed his ways, and if there was anything he could do to make their lives better now, he declared, he would do it.

They sat in amazed silence for a few minutes. Then Grandma remembered, to Joe’s astonishment, that today was his birthday. They sang the Happy Birthday song again, somewhat tunelessly and altogether anachronistically, and they laughed and drank some dilute and lightly fermented beer.

In a different fairy tale, Grandma and Joe would have then become betrothed. But Grandma had discovered, in the years of her widowhood, that she liked her family of women better. She thought Woodcutter Joe was a Perfectly Nice Guy, and she was grateful for his clever axework and his literacy. But she didn’t want to marry him. If the women’s hunger and poor circumstances at the inn had gone on much longer, she might have changed her mind. As it happened, though, Grandma’s resourceful family had something else in mind, involving both the Wolf’s missive and the apparently marriageable stranger.

* * *

The next morning Renee visited the town square. The Wolf knew at once who she must be. He trembled, imagining he was going to have to confront on a much deeper level the wrongs he had committed, and apologize to Miss Riding Hood without the mediating force of a piece of paper between them. For all the good emotional work he’d done, he had never stood face to face with someone he’d previously wronged. The others, who had helped the Wolf compose his letter, watched with interest.

But Miss Riding Hood was all business. She had come to take him up on his offer. Within minutes, and with very little discussion of the emotional portion of his letter, Renee had got what she wanted.

That evening, the stranger returned to the inn to inspect his prospective bride. The man did not recognize Renee any more than he had known her mother. As he sized her up, Renee saw in his eye a particular gleam. It reminded her of the Wolf’s yellow eye as he had lain in Grandma’s bed. The man was feigning indifference, but Renee knew, from that gleam, that his assessment of her might make him a little careless of his fortune.

He opened her mouth and peered at her good enough teeth. “All right, then,” he said. “She’ll do.”

“I’ll need you to attest to your bloodline,” Mama said. “I’ll send someone.” The stranger shrugged, unconcerned, and they set the wedding date for a week hence.

When the man got home, our Wolf, in the garb of a civil servant, was waiting at his doorstep. He and two others were there to take testimony regarding the man’s family tree. The fellow must state for the record the names and birthplaces of his parents and grandparents and swear on a Bible he was in no way related to the young woman whom he was to wed.

* * *

Red Riding Hood, meanwhile, put her dexterous young fingers to use sewing a gown and ruff. I wish I could put her in a powdered wig, too, but powdered wigs would not come into fashion for several centuries yet. Instead she tailored a cornered cap to suit the moment. A few days later when she arrived at court to present her case, she was every inch the barrister, in a triumph of cross-dressing worthy of Shakespeare, two hundred fifty years before the Bard set pen to paper. There she argued that the man who had laid claim to her family’s land and cottages was no heir to her grandfather’s estate, but an imposter. She called three civil servants who’d witnessed him swearing he was not a member of the Riding Hood family. She even threw in a de donis conditionalibus and a feodum talliatum or two.

If the barrister who called himself Rene (one “e”) possessed a strangely high voice, and if his face was hairless, the judge did not trust his own eyes and ears. He attributed Rene’s appearance to youth, soon to be cured with dreary years before the bench. That Rene fit so awkwardly in his gown, that Rene’s ears were delicate and hardly stuck out from beneath his cornered cap, aroused no suspicions. Expectations could defy experience. People often doubled down on their beliefs, in spite of themselves.

The judge ruled in Rene(e)’s favor, and soon the Riding Hoods had reclaimed their land, two cottages and brewing equipment, and were back in business for themselves (and they broke off the engagement with the stranger).

So it was that Rene(e) saved herself from marriage, and saved her mother and grandmother from hunger. The women remained on good terms with the Wolf. They continued to visit Woodcutter Joe on his birthday. And they lived out the rest of their lives with one another.

And though their story is a fairy tale, there have been throughout history real people like the Riding Hoods, and like the Wolf and the Woodcutter, too—people who could envision selves outside the Glick and Fiske paradigm. Our ancestors were walking that unnamed path in the woods a thousand years before our tale begins, and through the 1350s, and up into our time.

But you already knew that. You knew it even though you didn’t know you knew it. All this time, it’s been hiding in plain sight.

Jan Underwood

Jan Underwood is the author of a satirical, magic realist murder mystery, Utterly Heartless, and two collections of short stories. She has a new novel coming out at the end of this year set in a fictitious Latin American country. Jan lives in Portland, Oregon, which, with its endless rains and offbeat culture, has inspired the quirky settings of her books. You can learn more about her work at funnylittlenovels.com.