SILK

by Elizabeth Smith

It was almost midnight, and I’d been traveling over 24 hours since leaving my home in Louisville, Kentucky, when I got off the bus at Shinjuku station to meet my textile instructor, Bryan Whitehead, by the payphones. What I didn’t realize when I agreed to this plan was that close to 4 million people pass through Shinjuku station a day, and as I dragged my luggage through the endless sea of travelers to the first sad relic of a payphone I could find, I began to question my blind willingness to participate in this extreme trust exercise. I was dependent on one man finding me amongst millions in a real life version of Where’s Waldo: Japan Edition. Unfortunately for me, while Waldo could hang out on the bookshelf until he was found, I would be urban camping on the streets of Tokyo, waiting to be kidnapped.

image by Héctor García via Creative Commons

What person in her right mind would travel halfway around the world with such little forethought, you ask? One who is singularly focused on studying silk processing techniques for the purpose of reeling threads to dye with plants and weave into luxurious fabrics for clothing and interiors, that’s who!

I didn’t come to this ethereal Garden of Eden Haute Couture dream by some divine intervention or childhood calling. In fact, growing up in the Chicago suburbs, I had almost no relationship with nature, plants were irrelevant to my life and, more unique to me than my environment, I could care less about clothes. But I always loved making things and had an innate appreciation for Native American crafts in particular. Somewhere deep down inside my aesthetic psyche, I recognized that everyday useful objects had both an elevated and understated beauty when made from plants, animals or minerals. It wasn’t until I became a student host at the John C. Campbell Folk School that I learned to make my own art materials from nature and decided to focus on textiles as my craft.

My epiphany came during my first week in North Carolina at the Folk School, in Martha Owen’s class on knitting, spinning and natural dyeing. I was 22, and signed up was because I wanted to knit a pair of mittens for a red-headed boy I had a crush on. While I had my own agenda, Martha had hers, and in the first hour I watched as she took a seat in front of her spinning wheel and began to trot in place on her double treadle Ashford, making a fine thread from a puff of white fiber on her lap. When the puff was nearly gone, her assistant replaced it with a live white rabbit and Martha continued spinning, straight from the bunny! In the end, she had a beautiful skein of Angora yarn that was dyed in a bath of Marigold flowers to give it a deep golden hue. After spending the next four days working with fibers from flax, cotton, yak, sheep and silk, as well as dyes from lichens, mushrooms, roots and bugs, my generic mitten pattern and pre-purchased acrylic yarn didn’t seem so cool anymore. Martha’s agenda to inspire a new generation to farm, garden and foray in the name of fiber art had worked. I was a convert.

Fast forward to Japan. I was slowly coming to terms with my destiny to live out the sequel of Liam Neeson’s Taken, when Bryan emerged from the crowd of Japanese natives, standing out amongst thousands as the only blue-eyed Canadian in pink skinny jeans.

“It’s so good to see you again!” I exclaimed, both relieved and thrilled to be reunited with my silk working sense (and in that moment, savior). To be fair, I wasn’t a complete lunatic to entrust Bryan with both my well-being and textile education. We had met two years earlier when I traveled to Vancouver to take his course on indigo dyeing as part of Maiwa Textile’s annual fall workshops.

I was one of twelve ladies who joined the class to learn organic methods of indigo dyeing (without the use of hydrosulfate) from this 50-odd year old indigo farmer. Bryan had moved to Japan in his mid-twenties, eventually renting a three-story silk farm house in Fujino, a town historically known for silk raising and tea growing, and now more for its artisans and Waldorf schools. He spent thirty years tirelessly learning ancient Japanese textile practices from aging local artists and farmers who realized that their skills and traditions were dying off from a lack of monetary rewards and general disinterest from younger generations.

Over time, Bryan became an accomplished Shibori and Katazome artist, which complemented his Indigo growing work, but it was a serendipitous encounter with an old woman that brought his attention to silk. Like most living and working in Fujino during the early 1900’s, she raised silk worms and sold silk threads to the Japanese government, who used to be the number one exporter of silk around the globe. China has since taken over the number one spot (cheaper labor), which led to the death of silk farming in Fujino, but this woman continued to farm, regardless of its irrelevance in Japan’s changing economy.

Bryan spent the next six years visiting her home and learning every aspect of silk raising he could. Only the freshest, crispest Mulberry leaves would produce happy, fat worms and high quality cocoons. The leaves must be laid directly on top of them, because just an inch or two away and the worms would die of starvation. Some may be critical of silk processing because the worms are killed while in the cocoon, but if it wasn’t for human intervention, they wouldn’t make it past their first few days of life. If allowed to mature into moths and break free of their cocoons, they only live to breed, not having the ability to eat or drink, leaving behind destroyed luxury fibers for a few days of fornication.

image by Boston Public Library via Creative Commons.

With all the silk threads he was now producing and dyeing, Bryan decided to learn to weave. He taught himself to warp a loom and make fabric for kimonos, drawing inspiration from weavers like Shimura Fukumi and Chiaki Maki. He brought his bolts of fabric to Lichtenstein for an art show and they sold out within the first hour.

All of this was unbeknownst to me as I dutifully stitched my cotton cloth for Indigo dipping at the Maiwa workshop, until Bryan called us around the table to give a little show and tell of his work. That’s when he pulled out THE shirt, and my textile ambitions came into focus. He brought out a hand sewn, hand woven, plant dyed, home spun, silk shirt from the cocoons he had raised, and casually laid it on the table. In my own made for T.V. movie, this is when the music would play, the light would shine and my face would change. While Martha Owen was the one who introduced me to the world of natural fibers and dyes, Bryan was the one who showed me what I wanted to make with them. That shirt booked my ticket to Japan and had me riding alongside Bryan to his silk farm house for 16 days of in-depth study on silk processing and weaving.

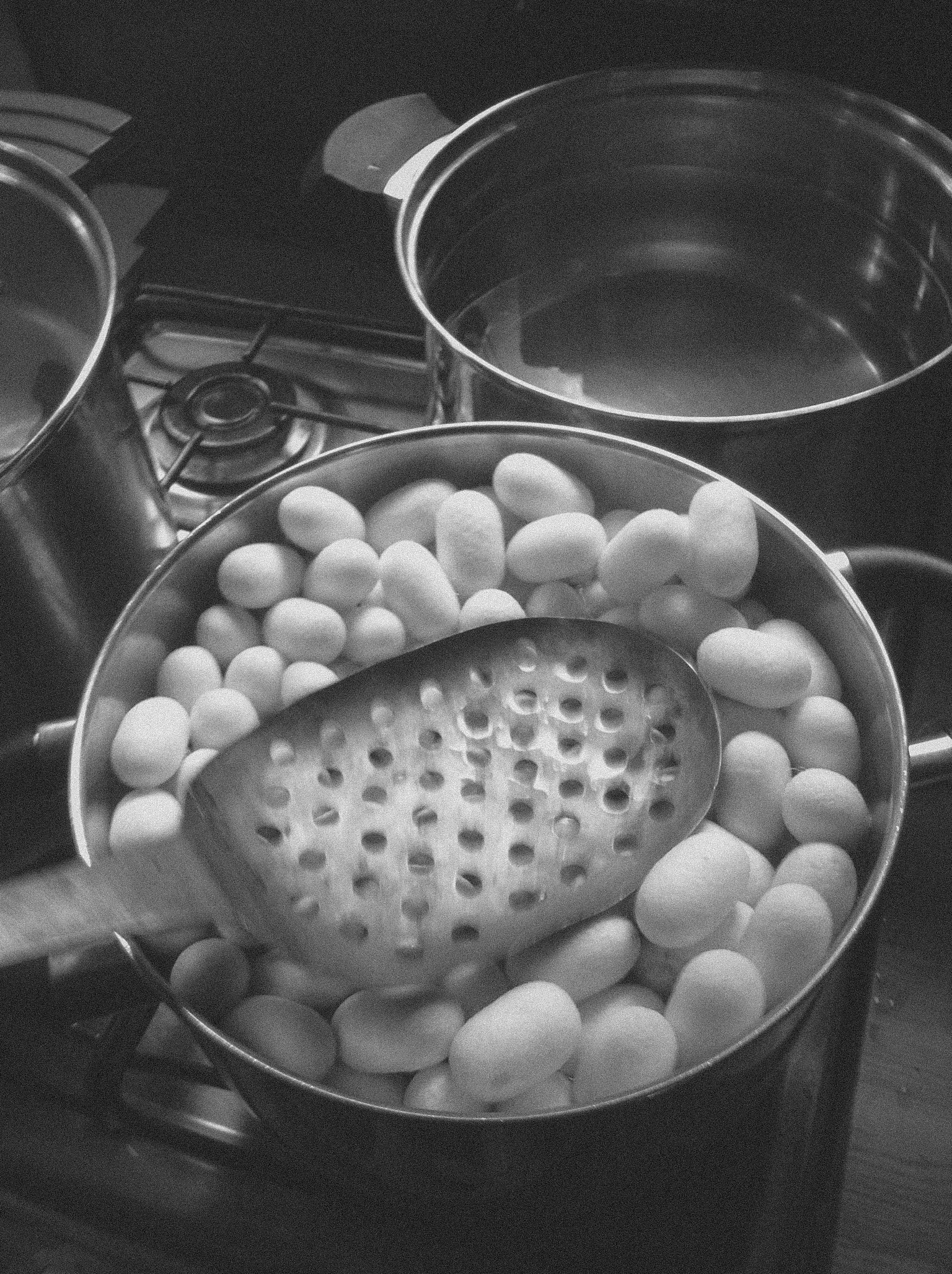

There are three main ways to make a silk thread: reeling, spinning from hankies and pulling threads from ‘jellyfish’. Reeling is finding the start of the silk thread on one cocoon and combining it with the threads from other cocoons. A silk worker will reel threads from 10-500+ cocoons at once to make a thicker thread because a single cocoon thread will break too easily and is impossible to weave or knit with. Reeling continues until the threads from each cocoon are almost out, unveiling the chrysalis inside each one. Once the silk has been reeled, it needs to be spun to ensure the thread stays intact and doesn’t fall apart into fluff.

To make silk hankies, lime is added to a pot of water to raise the PH level to 10. 50-100 cocoons are enclosed in a mesh bag and submerged under the simmering lime water for a little over an hour, or until the cocoons are fully collapsed. The increased PH level will de-gum the cocoons and soften the thread. The more gum that is removed from the cocoons, the softer and shinier the silk will be. Once the cocoons are fully collapsed, they are removed from the pot of simmering lime water and released from the mesh bag and into a bowl of clean water to be rinsed. This is where things start to get gross. While the collapsed cocoons sit in the bowl of clean water, a silk worker needs to pull apart each softened cocoon to remove the chrysalis and shed skin of the silk worm. Then the wet silk fluff from a single cocoon is stretched over a hankie maker, creating rectangles of silk fiber that can be spun into thread.

Finally, there is the ‘jellyfish’ technique, named for the cocoons’ physical likeness to the tentacled creatures during the thread making process. The steps are the same as making hankies, except the cocoons are removed from the lime water when they are partially collapsed and still somewhat firm. After rinsing, the cocoon is ripped open at one end and the chrysalis and shed skin of the silk worm are dumped out. Then, while still wet, fibers are pulled from the cocoon into a thin thread, as if to spin. When the entire cocoon has been pulled into thread, it is then knotted together with other pulled threads until a long skein of silk has been made.

Why all the different processes? Why does it matter? Each technique, along with the amount of degumming and number of cocoons used, results in a different texture, consistency, weight, thickness, shine, and more. There are endless combinations that can create endless amounts of different fabrics or just one very unusual piece of fabric. It’s these nuances in thread production that have such a profound effect on the aesthetic of the final product that I find so exciting.

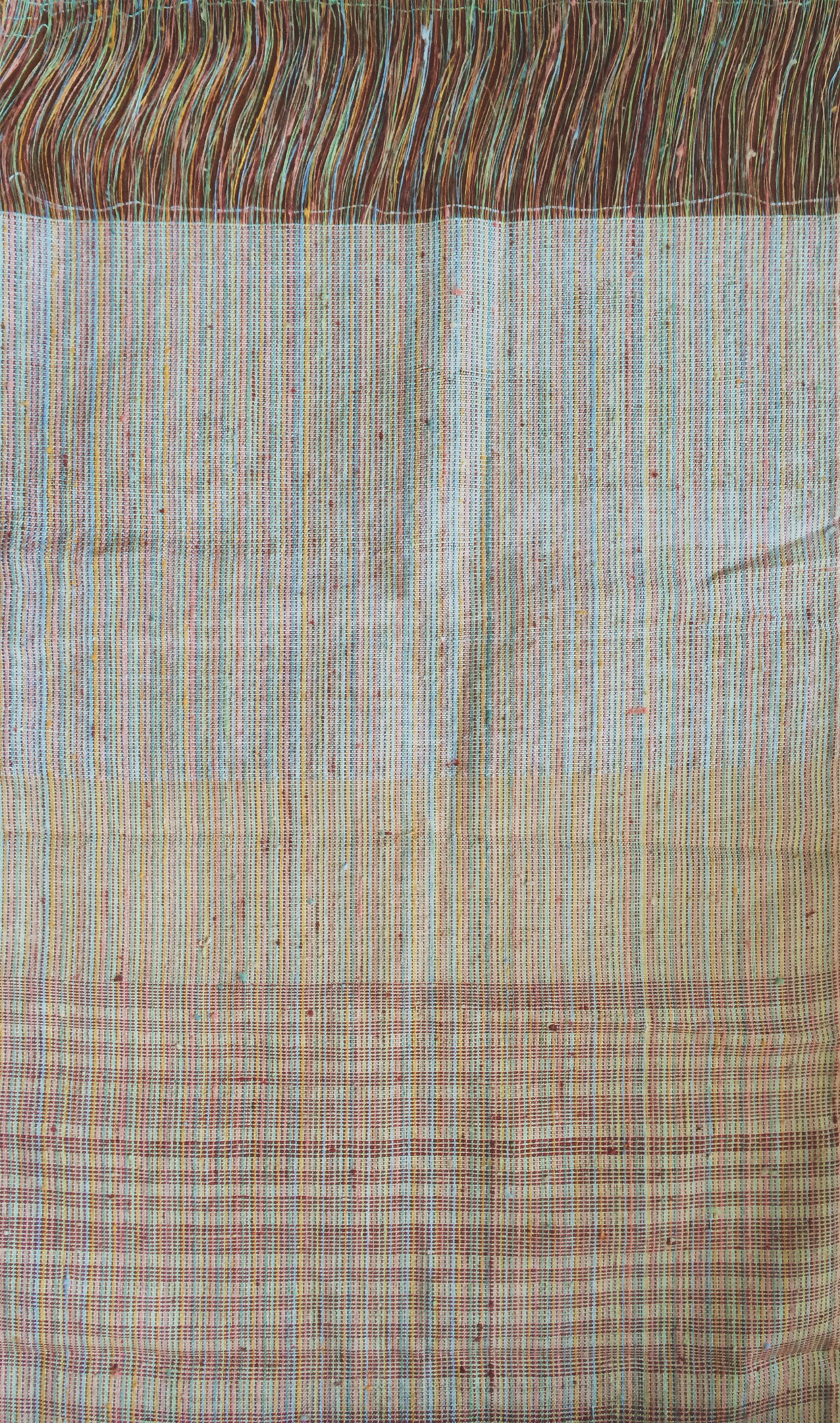

With Bryan’s guidance, we dyed our reeled and spun silk with madder, gardenia pods and indigo, achieving different colors by overdyeing one color with another or adjusting the amount of plant matter in each dye pot. We warped the loom with streaks of red through every other heddle, giving the overall sampler a crimson lined and dotted affect, made more or less severe by the color weft I chose to weave with.

I returned to Kentucky not only with my own cocoon to fabric sampler, but with a brand new silk reeler, skein winder, 1kg of cocoons and a head whirling with a zillion different project ideas to attack with my newly-purchased arsenal. I’m back in my apartment, surrounded by the usual spinning equipment, tubs of fiber and one abused lint roller. My twenties were dedicated to thread making and dyeing, an obsession fueled by a vision of brilliantly colored skeins of yarn, so beautiful and vibrant that they continue to live and breathe as they did in the gardens, forests and pastures they grew up in. I’m excited to dedicate my thirties to giving these threads yet another life, as part of the pillows we rest on, the shawls we warm up in and the blankets we sleep under.

Elizabeth Smith

Elizabeth Smith is an enthusiastic textile artist interested in raising and growing both fibers and dyes to knit and weave into fabric for clothing and interiors. She is the Visual Arts Director at the Cabbage Patch Settlement House in Louisville, Kentucky and teaches various forms of Textile Arts at private schools, art museums and community centers.