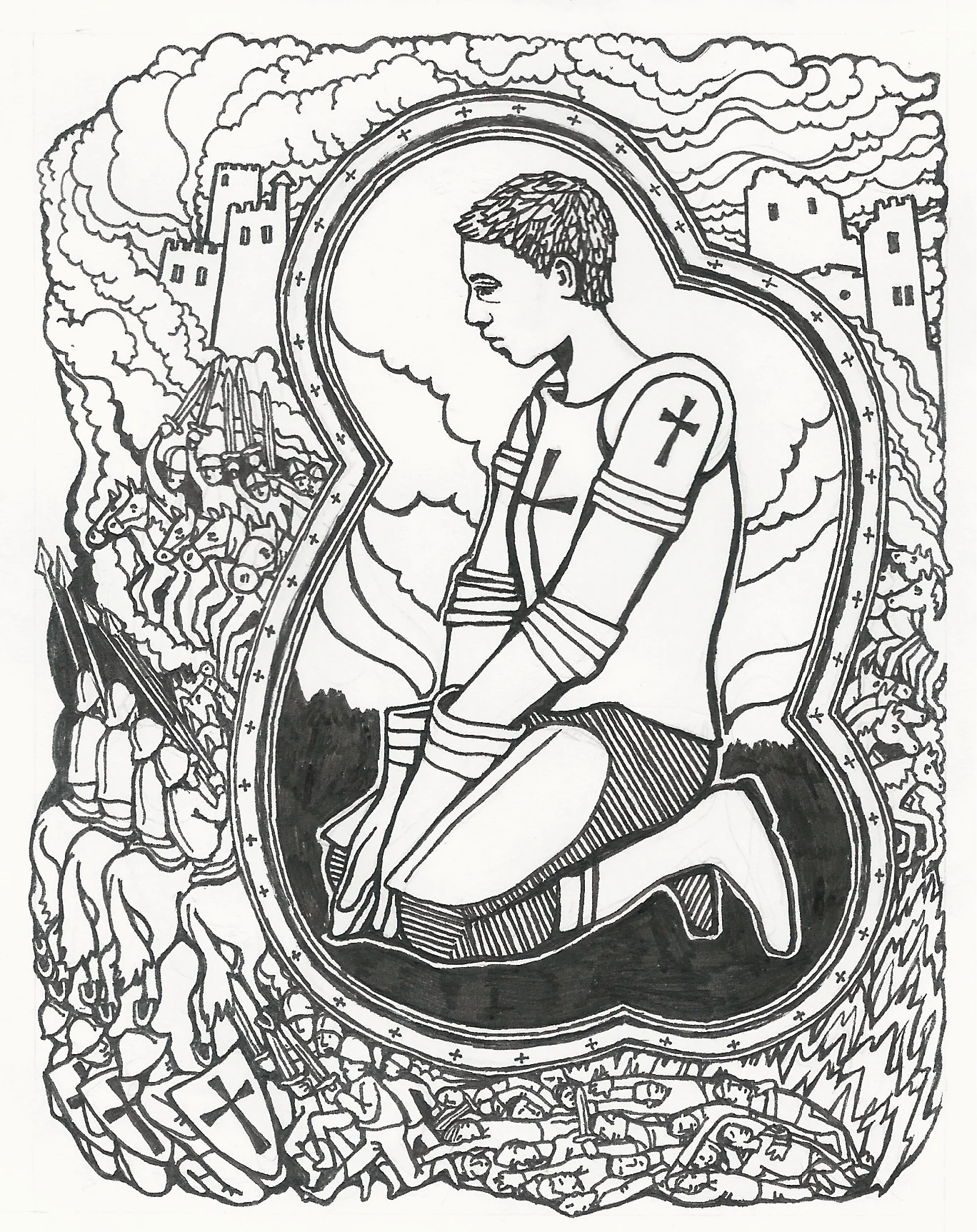

St. Joan

D.L. Mayfield

illustration by chris clother

I was thirteen the first time I cut off all my hair. I was young and rash and after it was cropped close to my ears I promptly bleached it to an electric orange. Joan of Arc, with her pageboy haircut and shiny, silvery armor, was my first true idol. Born and raised on missionary biographies and grand Biblical narratives, I found it an easy leap to fixate on Joan as a personal hero. I adored her story, choosing to focus only on the glories: her bad-ass way of circumventing all the constraints against females in her day, her devotion to God, her purity of mind and mission to save her friends and neighbors and country from the oppressors. I wanted to ride in on a horse and save France; I wanted to be idolized, my likeness encased in bronze. But more than anything, I wanted to be used by God.

I taught myself how to play the electric bass and conscripted a few friends and family members to start an evangelistic punk rock band (tagline: Christians can be punks too). We roamed small town youth groups and 90s-era coffee shops of northern California for a few years, singing songs about forgiveness and love and Jesus to kids who really just wanted an excuse to throw their bodies around for a moment. The short hair, the thrift store clothes, the spiked bracelets, the missionary lyrics: all of it pleased me to no end. The world is a war zone, and good soldiers are needed all around. And you never know when God might need to use you, the shy and determined zealot with thick-cut blonde bangs, to save us all.

I was twenty-one the second time I cut it off, shorter this time, barely an inch long all around. At my third college in as many years, working minimum wage jobs making over-priced coffee for the wealthy, trying hard to hear the voice of God. I would take breaks from my “soul-crushing” work and sit outside, a journal and pen poised in hand, ready to hear and do the will of the Lord. I ran my hand over my shorn head, hoping the extreme gesture would be mistaken for a sign of internal strength. In reality, it spoke to my impulsive, desperate ways, and my sadness at being found trapped in a very normal life. I was surrounded by other very normal suburban lives; people who, if they ever thought about a higher power at all, were prone to believe in a very calm and abstract presence: a God who believed in beauty, and order, and light; a God who had time to consider the beauty of a lily. But inwardly I wondered: who can think about lilies when the world is on fire? Like St. Joan, all I could see were the empty bellies, the growing unease, the wars and rumors of war. I was ready to fight it all, ready to take it on my small and determined shoulders.

So, in the absence of streams of light coming down from heaven and a voice whispering in my right ear, I went out and tried to fight the troubles of our age on my own. I started volunteering with recently arrived African refugees, jumping wholeheartedly into the fray of advocating for those on the margins of American society. The busier I was, the more I glowed: teaching ESOL classes, running homework clubs, shouting down predatory loan lenders, navigating the tangled halls of social services for my friends. I moved in with them, living in low-income apartments and experiencing life as a member of their community. A veil was lifted off of my eyes as I started to see first hand some of the battles that those experiencing poverty in America fight every day. Racism, classism, the crushing burdens of the increasingly unattainable American dream. The God I knew did not want any of these things for his/her children; armed with the truth that a better world was possible, I ran head-long into this experience determined to save everyone. In the end, of course, I didn’t.

The last time I cut it all off, only a few years ago, was different. A change was coming, and I could feel it. This time I cut it thick and soft and curling around my face. I let it be, light brown and wavy. I became pregnant with my daughter, my face growing rounder and rounder with no long hair to hide behind. As it grew out, it became another way to mark the passage of time, to know that things will not always stay the same. From the endless, sleepless nights of newborn-land to the repetitious snuggle-and-plead years of toddlerhood, my hair grew longer and longer. I looked in the mirror and the girl who stared back at me was a stranger. She was so heart-breakingly plain, down to the circles under her eyes and the messy brown ponytail hastily affixed. It was hard not to notice how far I had drifted from the image of St. Joan—the image of myself—I had crafted in my mind.

My daughter is now small and strong and determined; we are planning her fourth birthday party as I write this. She wants a pink cat piñata and she wants cups and plates with bugs and worms on them and she wants to invite everyone she has ever met in the entire world to come and eat cake with her. A few months ago I cut her hair, short and blunt and framing her face. Her blond hair springs into messy curls in the humidity and heat of summer, and wherever we go people coo at her. She looks like the spitting image of me at her age. She looks like a tiny, golden, Joan of Arc.

And it is this thought that give me pause, makes me reconsider how I have viewed myself all along. It makes me wonder at the narratives we tell ourselves, tell our children, tell our world about what it means to change anything at all. That we need to be bold, and fearless, prone to taking up our swords and then viewing ourselves as a savior. Time has started to teach me that for every hero there are a thousand more nobodies waging peace all throughout our neighborhoods. And in contrast to the grand, mythological narratives of our culture, the true victories seem to come through the plain and the normal, the opposite of our idols. Through people who walk the line between fervor and desperation, who are hopeful and unhinged. People who know that they are loved, and who walk in the paths that this opens up for them. This, more than anything, is what I truly desire for my daughter.

I am a girl who grew up always wanting to be Joan of Arc, and that seed is still within me. I hunger for peace and justice and reconciliation in our world; I also want to be recognized and valuable, short-haired and shining like the sun. My life, in the end, did not turn out to be anything like my beloved St. Joan. But I am now starting to realize that to God, she was only ever just simply, Joan.

image by krispin mayfield

D. L. Mayfield

D. L. Mayfield lives in the exotic Midwest with her husband and daughter. Recently they joined a Christian order amongst the poor, where they are currently seeking life in the upside-down kingdom. She likes to write about refugees, theology, gentrification, and Oprah. Mayfield has written for McSweeneys, Geez, Curator, Christianity Today, and Conspire! among others. She writes and curates a blog at dlmayfield.wordpress.com.